“With Each Passing Breath”: Documenting Japan’s Classic “Rōkyoku” Narrative Singing Tradition

A documentary film by Japanese director Kawakami Atiqa delves into the world of rōkyoku, telling the intimate story of a group of female performers preserving the narrative singing style, even into old age.

Rōkyoku, narrative ballads rhythmically intoned by a singer to the accompaniment of a shamisen, emerged as a popular form of entertainment during the Meiji era (1868–1912). Also known as naniwa-bushi, the genre developed from traditional styles of oral storytelling like jōruri that date back centuries. It joined kōdan and rakugo as the other dominant narrative forms of the period, enjoying broad popularity well into the early twentieth century.

Performances are lively affairs. At center stage is a rōkyokushi (singer), who spins melodramatic yarns made up of rhythmically sung sections (fushi) and spoken narrative (tanka). A kyokushi (shamisen player) provides musical support and helps maintain a dramatic atmosphere throughout the piece. The genre’s extensive catalog of songs borrows largely from historical events, folk tales, and well-known stories that are richly interwoven with themes like loyalty and the conflict that arises between duty and human emotions.

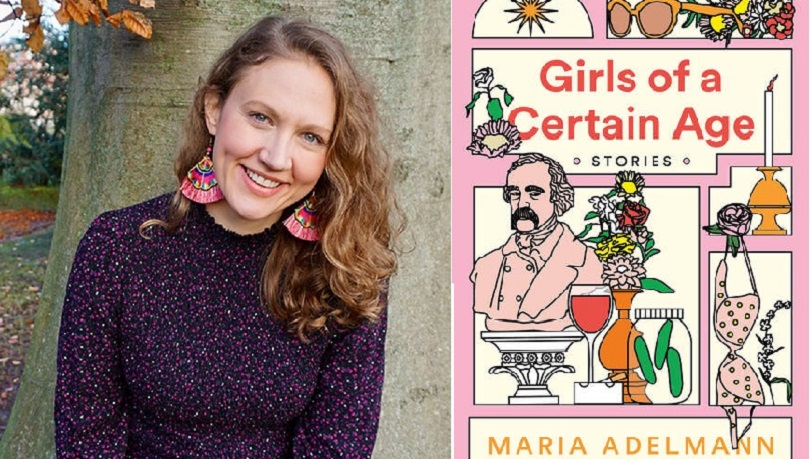

Renowned rōkyokushi Minatoya Koryū. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Rōkyoku waned in the early decades of the twentieth century but came roaring back at the start of the Shōwa era (1926–89), buffeted by the spread of records and radio. In 1947, seven of the top earners in the entertainment industry were rōkyokushi. At its peak, the genre boasted some 3,000 singers, many of whom, including the likes of Minami Haruo and Murata Hideo, went on to successful careers in enka and other styles music.

As new types of entertainment took center stage in the postwar years, though, rōkyoku‘s star faded. Today, there are only around 100 singers and shamisen players still active. Many are getting along in years, as are fans of the style of music, raising the specter that rōkyoku will eventually fade away completely. A recent revival of storytelling forms has allayed these concerns to a degree by infusing rōkyoku with new talent and drawing younger crowds to performances.

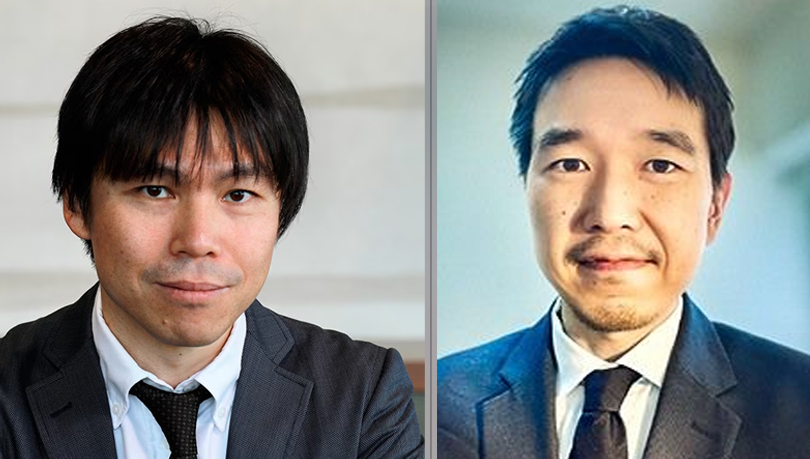

Starting in 2014, documentary film director Kawakami Atiqa trained her lens on rōkyoku, taking her camera into performance halls, practice rooms, and even the lives of performers. The culmination of her five-year endeavor is Zesshō rōkyoku sutōrī (With Each Passing Breath), a film that paints an intimate portrait of the artists who inhabit the dynamic world of rōkyoku. We sat down with the director and discussed her approach to documentary film making and other topics.

Encountering a Legend

Kawakami admits that she knew nothing about rōkyoku until she was introduced to it at a folk music event by a fellow concert goer who encouraged her to stay and watch the legendary rōkyokushi Minatoya Koryū. Kawakami followed the advice and was bowled over by the performance.

Born in Saga Prefecture, Koryū started her career as a rōkyokushi in 1945 while still a teenager. She spent four decades touring the country, but from the late 1980s she appeared mostly in Tokyo and other areas in the Kantō area. Kawakami says that enduring the tribulations of life on the road imbued the singer’s storytelling with a powerful, artful flair that set her apart from her sedentary contemporaries playing regular gigs in the city. “Her voice emanated from somewhere deep inside her,” describes Kawakami.

In 2014, Kawakami filmed a solo show by Koryu, turning it into the 33-minute film Minatoya Koryū In-Tune. In the work she attempts to capture the essence of Koryū’s stage-presence, but admits the difficulty of doing this with a single live performance. “There were so many aspects central to her art that didn’t come through in the final work,” she explains. “Things she carried inside her that don’t come to the fore on the stage.” Koryū was already in her late eighties when Kawakami began filming, filling the director with an added sense of urgency. “I wanted to document as many performances as I could.”

Koryū, right, hugs shamisen player Sawamura Toyoko after a performance. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Getting in Close

In creating With Each Passing Breath, Kawakami widens her focus from Koryū to present a rich cast of characters involved in rōkyoku. Central to the tale is Kosome, Koryū’s younger apprentice. A former traditional street musician, she is still learning the ins and outs of rōkyoku when the film opens.

In filming, Kawakami does not remain a distant observer. “I wanted to show the intimacy of those involved in rōkyoku,” she says. A stunning example comes in an early scene at the cramped, two-bedroom apartment of veteran kyokushi Tamagawa Yūko. Koryū stays at the residence on the outskirts of the Tokyo whenever traveling to the capital from her home in Aichi Prefecture. Kosome is a regular visitor as well, coming to train with Tamagawa, and we see the two absorbed in a lesson.

“Kosome had been Koryū’s apprentice for less than a year at this point and is eager to learn more about rōkyoku,” Kawakami explains. The director, spurred on by her own enthusiasm, does not hold back but places her camera alongside the pair, saying that “at times it felt as if I was part of the lesson.”

Tamagawa Yūko, right, instructs Kosome at her apartment in Akabane. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Tamagawa, who turned 100 in 2022, is another of the film’s key figures. The widow of acclaimed rōkyokushi Tamagawa Momotarō, she is the oldest performer at the Mokubatei theater in Tokyo’s Asakusa neighborhood, Japan’s only dedicated rōkyoku hall. Boasting a career spanning eight decades, she is a vital link to the history and traditions of the narrative art.

The film begins in the mid-2010s and features several of Koryū’s later appearances. Although suffering the effects of age and in poor health, the veteran singer is still able to captivate audiences with her vibrant, compelling performances.

The End of a Long Career

Time inevitably catches up with Koryū, though. In a moving scene, she movingly admits that after 70 years as a performer that her career is at an end and retires. Kawakami recounts that she was floored by this sudden turn of events, describing Koryū’s pained decision as “a historic moment.”

Koryū and Tamagawa share a moment with the other resident of the apartment, her cat An-chan. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Later, Kawakami travels with Kosome to Inuyama when she visits Koryū, whose health has worsened. To raise her bedridden mentor’s spirits, Kosome plays a cassette tape of Koryū’s old performances. The twang of the shamisen and powerful vocals stir Koryū, and she feebly begins to move her hands in time with the music.

A collection of cassette tapes of Koryū’s old performances. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Kawakami says that she struggled over this scene. “I set out to document Koryū, a master of rōkyoku,” she says, emphasizing the performer’s stage name. “The person convalescing there, Iwahashi Toshie, wasn’t part of that story.” Kawakami subsequently limits her intrusion to this one moment. “When she begins to move her hands to the music, it was as if her stage presence had been summoned. She transforms, with Koryū coming to the surface for a sublime instant.”

Passing the Torch

Kawakami says that over time she gradually shifted her focus from Koryū to Kosome. She foreshadows this change with footage taken of Kosome playing a three-tiered drum used by chindon’ya musicians in a scene shot at Tokyo’s Harumi Wharf. The film opens with this image, and Kawakami returns to it later—the only instance the timeline of the documentary is disrupted—as a narrative device to indicate Kosome’s emerging role.

Kosome performs at the Harumi Wharf. She set off on her own as a chindon’ya performer in 1997, and in 2013 she began studying rōkyoku under Koryū. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

The director does not say what happens with Koryū. Instead, she uses shots of Kosome walking alone through empty streets and looking longingly at cherry trees in full bloom to indicate her fate along with Kosome’s state of mind as she determinedly plods ahead despite the loss of her mentor.

Tamagawa had already started to take over training Kosome when Koryū stepped down from the stage, and the latter half of the film focuses on these two. “In a natural flow of events, they became the center of the story,” says Kawakami. “It illustrated for me how the community survives and the spirit of the genre is carried on.”

A Message of Resilience

In true tear-jerking naniwa-bushi fashion, the story concludes in 2019 with Kosome making her formal debut at the Mokubatei as a full-fledged rōkyokushi. While there was little indication when Kawakami started her project eight years earlier that it would conclude in such a dramatic climax, by the end of the film it seems an almost inevitable outcome. However, Kawakami insist that this was not her editing, but the natural flow of events. “I merely channeled what I saw into the film.”

Kosome, right, is joined by Tamagawa as she makes her formal debut at the Mokubatei. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Kawakami says that what started as a desire to document a legendary performer transformed into a study of the world of rōkyoku. Out of the gates, though, she finds the genre reeling from the sudden death of star Kunimoto Takeharu, a member of the younger generation of performers. Along with Koryū and Kosome, she documents other important performers like shamisen master Sawamura Toyoko, Tamagawa Nanafuku, and up-and-coming talent Sawamura (now Hirosawa) Mifune, who add to the narrative.

Kawakami has masterfully edited the mountain of footage she shot, some 200 hours, into a compelling 111-minute documentary, a task she says was helped along when society shut down during the COVID-19, providing more time to focus on her work.

“I poured eight years of my life into the film,” she says. “It was very intense and meaningful to be so intimately involved with people and their lives.” She is pleased with the reaction to the film so far and the impact it is making on audience members. “I hope it inspires even one more person to go out to a performance hall and experience rōkyoku first hand. In this age of online communications, such places still offer the authentic experience of sharing in the energy of others.”

Banners flutter outside the Mokubatei in Asakusa. (© Passo Passo/Kawakami Atiqa)

Source: Nippon

0 Comments