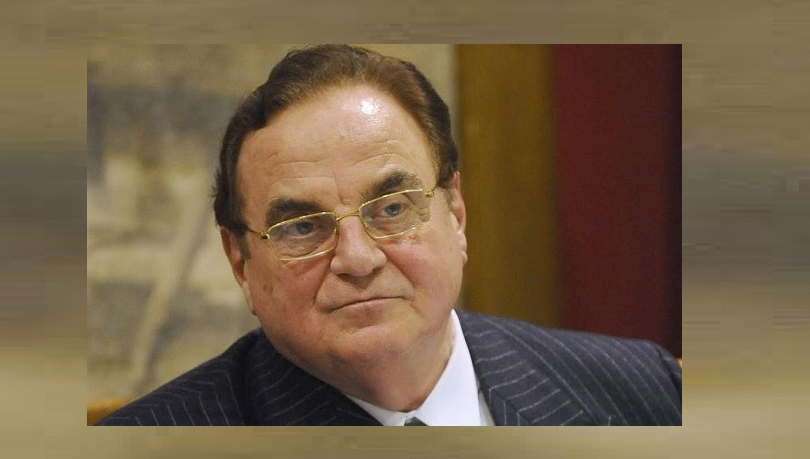

Dean Koontz is one of the world’s most prolific and best-selling writers, with more than 120 novels to his name. During a difficult childhood, books were his refuge, so he has devoted his life—6:30 AM to dinnertime, six days a week, for the past five decades—to creating fictional worlds across a range of genres for his devoted readers.

HBR: Where do you find your creative energy and stamina?

Koontz: It goes back to what books meant to me when I was young. I came from a very poor family. My dad was a violent alcoholic. Books were both an escape and a lesson that other lives were different. They showed me the level of success the world offered. And that was plenty of motivation to change my destiny. I realized that you can make what you want of life, and I don’t think I’ve ever stopped feeling that way. I’ve never stopped being excited about books and the potential of them.

So there’s never been a time when you’ve thought, I can’t keep doing this anymore?

If I wrote the same book every time, which is what publishers prefer you to do, I would go profoundly nuts. It’s a formula-driven business—if you’ve written one book about a bricklayer, they want you to write 1,000 books about a bricklayer—but I’m constantly changing things up. The advice has been not to do that, not to mix genres, not to try different kinds of storytelling, and I understand that. It’s more difficult to market a book that’s not like the book that everybody bought and enjoyed before. On the other hand, doing anything for as long as I’ve done this can lead to boredom, and change—going for something you haven’t gone for before and that you’re terrified you’re going to fail at—is how I avoid it. When an idea comes to me, and it seems too big to write, too complicated to convey to a reader, that’s when I’m most energized. The challenge is a medicine against boredom. It inoculates you.

How do you gauge the right level of creative risk to take?

I wrote a book many years ago called The Bad Place, with a character, Thomas, who’s a boy with Down syndrome. My agent at the time, after reading the manuscript, called me up and said, “The Thomas character is pure genius. I can’t believe you pulled this off.” And I said, “You know, I loved writing from that character so much I thought about doing an entire novel from the point of view of someone with Down syndrome.” She was silent for about half a minute, then said, “There’s such a thing as too much genius.” But I think you can pull off anything if you put your mind to it. Language is so flexible and beautiful and offers so many techniques to a writer.

You initially wrote under pseudonyms. When did you realize that your name carried currency?

In my early days, every time I did something a little bit different, which was most of the time, agents and publishers would say, “You must have a pen name.” I was naive, so I did. Then gradually I saw that something was happening around the books under my own name. I wasn’t a best-selling author yet, but we were getting 30 or 40 letters a week, instead of three or four. So in the late ’70s or early ’80s, my wife and I decided to buy back the rights to many of my books. We had to stretch ourselves, and other writers thought I was insane. Publishers would sell them back to me, but often at what they’d paid me for them, which meant that I had essentially done the books for nothing. But there were two reasons we did it. One, I had written a number of science fiction novels, and we knew that if they stayed in print, I would forever be a science fiction writer in critics’ minds. Once they label you, it takes years to get past it. So by buying those titles back, we were eliminating that danger. Two, we felt the other books would have ongoing value if I became a bigger seller. I remember one case where we went to the publisher of four of my books that I’d written under a pen name and asked to buy them back. I don’t know whether it was a bad day for him or he was just mean-spirited, but he said, “You can have them for nothing. They’re worthless anyway.” And rather than be insulted, we said, “Well, thank you very much.” And the very first one of those four that we released under my name spent six weeks at number one on the New York Times paperback best-seller list and sold two million copies in the first year. And that showed us that we’d been right. We could tell that enthusiasm was building. It wasn’t delusion. Then it was just slow, incremental sales growth and critical reception that started to be of a different kind.

It took 18 years to get from your first novel, Starquest, to your first best seller. Was that a frustrating wait?

It’s such a thrill to be published in the first place. If you’ve been dreaming about a life of books since you were a child, you can go for years on a modest level of success and feel perfectly comfortable. But it was frustrating later on when I felt that certain books had what it took, but we weren’t getting the support to make it happen—or when we would have a paperback best seller, but my hardcover publisher would say, “Oh, you’ll never have a hardcover best seller.” Eventually I understood that success requires the support of an agent and publishing, and I had to move at various times in my career—not out of agitation or anger but just when it became apparent that change was necessary. Sometimes it’s painful to do, because you’re leaving people you’ve come to like very much. But it’s not them, it’s the system that isn’t working for you anymore.

When you have a hit book, is there huge pressure to do it again?

My first book to reach number one in hardcover was called Midnight. My publisher called me and said, “I have wonderful news.” But before I could say, “Whoopee!” she said, “Now you must understand: You do not write the kind of books that can be number one, and this will never happen again.” And my balloon of excitement was deflated in an instant. We had four number-one books after that, and she said the same thing every single time. So at first I didn’t have pressure to keep it up; instead, I had to keep proving myself. Finally I said, “I have to go somewhere where they think it is going to happen again.”

What is your approach to working with editors?

Working well together is crucial. I had one situation in which I was very excited about a publisher and editor, then discovered I was getting editorial by committee—all kinds of notes that conflicted with one another. An editorial relationship has to be real and between me and somebody I respect, and I’ve been mostly fortunate in that regard. I know there are some writers who don’t want to take any direction. But even though I’m obsessive-compulsive as a writer—I rewrite every page 20 or 30 times before I move to the next one, so I turn in a pretty clean manuscript—I know a good editor can always spot things I haven’t thought of or make little fixes. And there’s no reason not to listen with an open mind: “Yeah, I could do that” or “No, I can’t.” It forces you to explain why you did things a certain way. And if you can’t, if something doesn’t have a thematic reason you can easily lay out, then you did sort of fudge it, and you’ve got to revisit it. If you can answer the question, it makes it clear that you did it for the right reasons. Now, my wife is my toughest and fairest critic. When she reads something and has a problem, I look at it in a very serious way. If she doesn’t have a problem, I feel more confident with it.

Your wife has played such a big role in your professional life. Is it difficult living and working together?

I know people who think it’s the sure road to divorce. But our offices are side by side in the house, so it’s 24/7—and I can’t imagine it any other way. One reason our marriage works so well is that we share the same sense of humor—ranging from dark to silly. We both know that there is almost nothing in life that isn’t funny in retrospect, and if you have that attitude, work and domestic issues don’t get as serious, because you know a month or a year or two from now, it’s all going to look very small. Also, she has a different set of skills and abilities than I do, so we fit together like a puzzle, almost. Her skill is accounting and numbers, and mine is not. I probably haven’t written a check in a year and very few over the past 50, and I never could balance a checkbook. So all of that’s lifted from me, and I get to focus more intently on what I do.

Your books have become more literary over time, but they’re still accessible. How do you find that balance?

I started out in paperbacks, a market in which entertainment comes first. But I think it should anyway. Dickens is enormously entertaining at the same time that he’s literary. I always have been in love with language, but over time it became a more profound love, and my books started changing. Of course, I can’t tell you how many times I was told to write with a lesser vocabulary because I was turning off readers. But in the quality of letters I get and at book signings, I can see that my readers are articulate and engaged, so I know who I’m writing for. When I was a young writer, I thought there were a certain number of tricks to writing, and once you learned all of them, the books would get easier. Actually, the books get harder because there are an infinite number of tricks, and the ones you haven’t learned yet are more difficult. Language is so pliable. There’s so much you can do with it, and it can be frustrating when your ability isn’t yet what you wish it would be. But if something comes out in a paragraph that is just what I wanted to say, just the way I wanted to say it, and I think it will resonate with a lot of readers, that’s the best, most exciting thing. It’s also exciting when you find yourself in a flow state. You can’t make it happen, but one day you’ll be sitting at the keyboard, and the words will come with a solidity and a richness and a texture that you usually struggle for, and suddenly there it is.

Tell me about your process from the initial idea for a story or a character to a published book.

I used to write from outlines. But when I wrote Strangers, which ended up having an enormous cast and being about a quarter of a million words, I decided not to do an outline and just start with the premise and a couple of interesting characters. I decided to wing it, and it was the best decision. I’ve never used an outline since. I start with a bit of an idea, a central theme, a premise, and then I think about it for a little while—not for weeks and months, but days—and then I begin. If the character doesn’t work in the first 20 pages, you might as well quit. If a character comes alive, I let the character move the story along. This is the hardest thing to explain to young writers. You tell yourself that you know exactly who a character is and try to make that character conform. If you give the character free will, the character becomes richer, more layered, more interesting. It’s the oddest thing, but it’s true. Characters can take over, and they will take books to better places than they would have gone if you’d set a template and written everything according to it. I do sometimes know a key thing about the ending or something at the center of the plot or a key scene here or there, but generally I don’t know much. I remember I was working on a book called The Face, and right in the middle of it a line came into my head: “My name is Odd Thomas. I lead an unusual life.” It was like listening to somebody speak, and I recognized it as an opening to a story. I keep a yellow, lined notepad to put down reminders, and I wrote the line down. And even though I never write longhand because I can barely read it, I found myself continuing to write, and hours and hours later when I stopped, I had the first chapter of the book Odd Thomas. And I knew it was going to be a series, even though I’d never written one before. And I sat for the longest time, wondering “Where did this character come from?” To this day I don’t know. But I wrote eight Odd Thomas books.

What does a typical workweek look like for you?

This will sound grueling, but it’s not. I usually get up at five in the morning, get ready for the day, walk the dog, read the Wall Street Journal. By 6:30, I’m at my desk, then I work until dinner. I rarely have lunch, because if I eat, I get furry-minded. I do that six days a week or, if I’m at the end of a book, seven. If it’s the last quarter of a book, where the momentum is with me, I’ve been known to work 100-hour weeks. That’s all normal for me because when I’m sitting at the screen for 10 hours or so, the real world retreats, and I fall away into the novel more completely. Sometimes I’m in some scene and laughing out loud or moved to tears, and people walking by my office door probably think I’m at the edge of losing my mind.

As a perfectionist who constantly revises, how do you ensure that you still make progress?

All I can say is, it works for me. I don’t know that it would for other people. Every time you go through a page, you’ll find ways not just to tighten but to say things better, with more vivid figures of speech. And there’s a momentum to that, too. You’re not necessarily advancing the story 10 pages a day, but you’re advancing its quality. And then, because this slows you down, you can recognize that you’re going to hit a problem 30 or 40 pages on. With my pace, I find that when I get to that moment, I have two or three ways to resolve it even though I wasn’t consciously thinking about them. Writers I know who don’t work this way, when they bump up against a problem, they can’t get around it. They have writer’s block. I never run into that. And I think it all has to do with this way of working.

How have you successfully navigated all the big changes in the publishing business?

I’ve watched things happen that publishers couldn’t possibly control, and I’ve watched things happen that they could have controlled but didn’t think they needed to. One of those was to let the paperback business basically die. There were once I think 500 distributors of paperbacks, and now it’s down to four or five. A lot of publishers never quite grasped the rise of ebooks. Last year, my agents made the argument that I would probably sell more books with Amazon than with anybody else. And one of the key things was its marketing proposal. We looked at eight publishers and some of them came with a one-page plan. Others came with eight or 10 pages. The Amazon plan was around 30, and impressive and thoughtful. So we did a contract for five books. Maybe some of the traditional publishing people think I’m a traitor, but all the ones I know, even independent booksellers, have said it was a great move.

You’ve described yourself as an autodidact. How do you keep up that constant learning?

In high school and even college, I was—and wasn’t—a slacker. The things I wanted to read and do were more important to me than what my teachers wanted me to read and do, so I would often fake a report—either I’d not have read the book or I’d make up the book titles for my bibliography. I never got caught. I just didn’t want to do research. When I was writing science fiction and fantasy, I had to have some basic scientific knowledge, but I could also just make most of it up. In contemporary fiction, though, you have to be sure you’ve got it right. I didn’t want to get letters from readers. So I started doing research, and to my great surprise, I found that learning about something new and being able to make it part of the story, to impart it in an entertaining way, was something I greatly enjoyed. I got interested in some pretty complicated things, like quantum mechanics, and I found that the more I taught myself, the more story ideas would come to me.

I read that you delegate some research, because you don’t want to get stuck down a rabbit hole that takes you away from writing. Is that true?

I don’t go online in my office. If I do, five hours later, I’ll still be on some site. But my assistants are online, so I’ll ask them to find this or that out for me. And then they’ll give me a printout. Or I may go and sit with them. But I always read and vet the research myself.

Have you made any big mistakes in your career?

I had one early agent I could have done without. I was already number one on the paperback best-seller list, and the terms I was getting in contracts struck me as very primitive. She kept telling me that things I was asking for could never be gotten. But I knew a writer lower on the best-seller list who was getting those very things. Either my agent didn’t know this—in other words, didn’t know her job—or was for some reason more interested in pleasing the publisher than the client. I stayed with her many years despite the suspicion that I wasn’t getting good representation, because I thought she was a great person. I allowed my feelings to smother my business instinct. For years, my behavior was that of the adult child of an alcoholic. I always thought, If I rock this boat at all, everything will come crashing down. It was a kind of disbelief that it could be working as well as it was. Before that, I was represented by an agent, who I also loved as a person, but I had to leave him, too, because he started shipping outlines back to me, saying, “I can’t sell this.” When I asked, “Why not?” he said, “Because you’re trying to write a bigger book than you can. You’re a successful midlist author, but you’ll never be a best seller.” And I said, “I’m 28. There has to be growth and hope.” There was a 14-year period when I had no agent, just an entertainment law attorney. But then the business began changing, and I needed some guidance, and I finally made the best connection I could have hoped for at Inkwell Management. So you can just keep trying, and it will work.

Do you foresee ever retiring?

I don’t know what I’d do if I wasn’t writing. It defines me. I love doing it. I do have a spiritual side, and I think that talent is a grace, an unearned gift. And it comes with an obligation to use it as well as you can.

Source: (https://hbr.org/)

0 Comments